Protons, neutrons, electrons, fees

Spin, charm, and strange, all have their place

In one atom’s snug mysteries,

Ode to the Atom by John Updike:

This is again the time of the year when many young school leavers are thinking of what path to take next.

In recent years there has been a concerted campaign by government encouraging students to choose STEM subjects over humanities to the detriment of humanities teaching, both in schools and universities.

Last week it was announced that the CSIRO will slash up to 350 full time jobs to address rising costs. It comes on top of more than 800 positions already made redundant in the past 18 months.

It’s understandable that many feel frustrated, or even cynical, when they see cuts to revered scientific institutions like the CSIRO and when at the same time they had been steered towards careers in science, technology and research.

First, a question stirs the quiet air,

A tremor in the stillness of the mind.

A shape half-formed, a possibility

That waits for evidence to make it shine.

We guess—but guessing isn’t where we end.

We test. We measure. Doubt becomes a friend.

For only what survives the trial of truth

Can be the seed from which our knowledge grows.

The Hypothesis

Despite a relatively small population, Australia has made global-scale contributions in a number of domains: medicine, materials, communications.

Think medical application of penicillin; the black box flight recorder; spray on skin for burn victims; polymer banknotes; WIFI wireless networking components and cochlear implants.

One wonders how Donald Horne would have responded to the current cuts.

In Donald Horne’s The Lucky Country (1964), his main argument was that Australia’s success has come largely by luck, not by the skill, intelligence, or vision of its leaders. In his usually misunderstood and misused quote that Australia is a Lucky Country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck, he argued that Australia’s elites were complacent, unimaginative and resistant to innovation.

He may well have added lacking in vision beyond the next election.

He warned that unless Australia developed better leadership, cultural maturity, and economic planning, its luck would not last.

Horne would very likely have been strongly critical of the CSIRO cuts.

He’d have interpreted them not as a financial necessity, but as a worrying sign that the country is failing to invest in its future intellectual and scientific capacity and in its youth.

He would despair to see Australia relying again on its natural “luck,” instead of building the deep, resilient institutions that can sustain long-term national development.

He might even have changed his ironic ‘Lucky Country’ view of Australia to a blunter assessment of it being a Stupid Country that continues to follow short term goals at the expense of future generations.

Harsh as it sounds, we are indeed stupid to accept an economic model that relies heavily on exporting raw minerals we dig out of the ground, shipping them to where they are value added and then returned to us at a high price.

So we export iron ore rather than steel, lithium concentrate rather than batteries, raw agricultural products rather than manufactured food and gas for which we end up paying through the nose for the refined products.

Meanwhile our best and brightest follow that well-worn path to countries where their talents are welcomed.

What’s happening is better understood as a long-running tension between political priorities and investment in science, innovation, and other long-term planning.

Even before the cuts we were employing fewer people in STEM manufacturing and research than other comparable countries.

So what incentive is there for young school leavers to aspire to science and research?

In the crucible of time,

Where elements collide and combine,

The catalyst of change whispers,

And new paths unfold

The Catalyst:

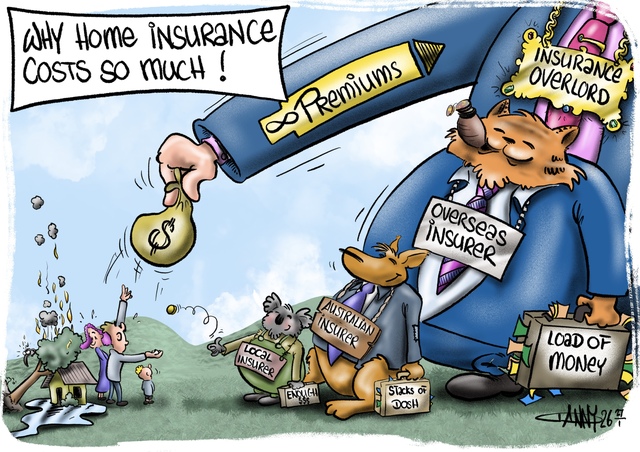

Moreover we are at the whim of what happens overseas and the health of budgets no matter what party is in power, is dictated by what we get for our raw materials.

Add to that the unhealthy presence of lobbyists from resource companies lurking in the corridors of our Parliament looking for favourable treatment from our elected representatives.

So when money tightens that’s when governments panic and start cutting back, Invariably, the first casualties are science, higher education, welfare and of course research.

There are few votes in research.

This vicious cycle has been repeated under multiple governments of both major parties.

And those newly minted school leavers struggling with decisions of what career path to follow may consider that we employ fewer people in STEM manufacturing and advance d technology than other countries.

It seems strange why we have managed our bountiful resources in such a profligate way and become captive to a cycle that repeats time and time again.

This aligns with Horne’s warning about over-reliance on what is immediately profitable or politically expedient, rather than building a mature, intellectually resilient nation.

And yet other resource rich countries have taken a different path.

When North Sea oil wealth was discovered, Norway established a sovereign wealth fund to channel surplus revenues into long-term savings rather than immediate consumption.

This allows its citizens a high standard of living without being exposed to volatile resource pricing.

Norway can afford to deliver strong public services in health, education, welfare, pensions.

Botswana was once among the world’s poorest nations but since Independence in 1966 as the world’s largest diamond producer has channelled the diamond revenue into education, healthcare, infrastructure, rather than purely consumption.

It has had current account surpluses over long periods and has transformed itself into a middle income nation.

A great example where the resource sector has not been allowed to distort politics or the economy.

This is directly in line with Horne’s belief that real national leadership should recognise that institutions like CSIRO are not just a line item — they are foundational to Australia’s future.

This keeps Australia dependent on exporting dirt while importing expensive finished goods — the opposite of how advanced economies build wealth.

This aligns with Horne’s warning about over-reliance on what is immediately profitable or politically expedient, rather than building a mature, intellectually resilient nation.

The cuts should not be seen just as cost-cutting, but as symptomatic of a broader strategic failure: not enough investment in institutions that matter.

And a dereliction of duty to the next generation.