Wurundjeri elders and descendents of William Barak are rejoicing after hearing the news that two of his artworks will be returning to Country after successful bids at a New York auction.

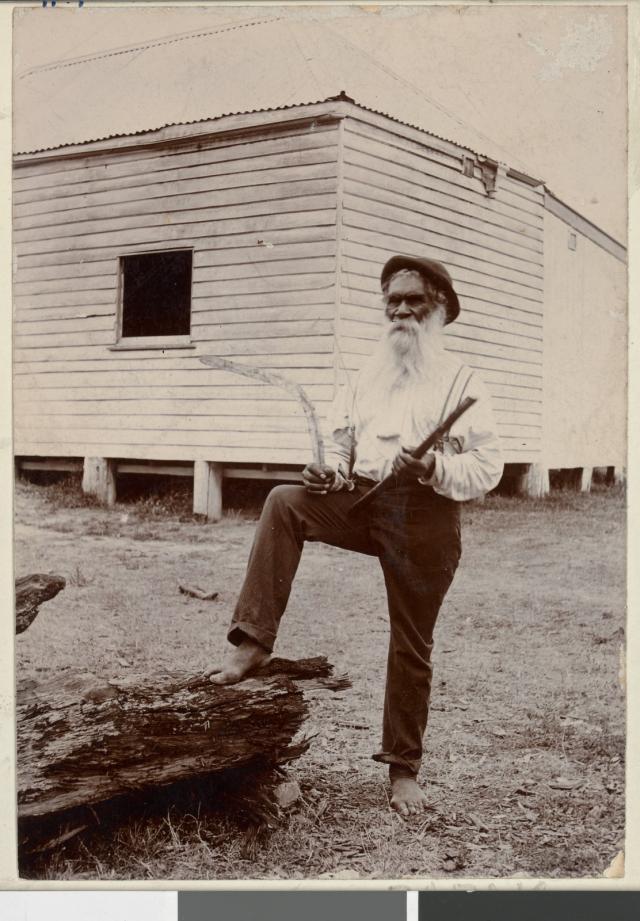

The rare artworks known as Corroboree (Women in possum skin cloaks) and Parrying Shield were made by the Aboriginal leader in 1897.

Sotheby’s, a New York auction house, put the works up for bidding on Wednesday 25 May at 4pm New York time.

Great, great, great niece of Barak, Jacqui Wandin said she was anxious waiting to hear the results of the auction having missed the part where Barak’s works were live streamed.

“There was that feeling of who bought it? Where is it? Almost like your family or a child. You want to know where it is and if it is safe. So that was a little bit of an anxious time,

“I then called my dad Alan Wandin and then he said, ‘Yep, it’s been bought by Wurundjeri’. So everyone’s just over the moon. We could not be any more happy.”

Having crowdfunded $120,000 via the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation GoFundMe page, it wasn’t enough to secure the works.

The Victorian government has announced it was proud to support the Wurundjeri Corporation in its effort by contributing $500,000, making the bidding a success.

“The Labor Government is proud to support the successful bid to bring artworks – which are invaluable to the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung People – back to their rightful home and owners,” Creative Industries minister Danny Pearson said.

“William Barak has had a profound impact on Victoria’s cultural heritage, with his contribution as an ambassador and advocate for his people continuing to have an impact today.”

Aboriginal Affairs minister Gabrielle Williams said these works will be returning to where they rightfully belong.

“We congratulate the Wurundjeri on their success in fighting for and securing this important piece of history, which is invaluable to the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung People, and to the broader Victorian public,” she said.

With over 1000 people contributing to the fundraising efforts, as well as the government support, Jacqui said it was important to recognise that there were a lot of “players involved in getting these beautiful artworks back.”

“We can’t thank people enough for stepping up and saying ‘this was the right thing to do. It’s now time. We need to celebrate William Barak more’,” she said.

Jacqui said these artworks speak of the time in Barak’s life in the 1880s and 1890s when his wife and son had already passed but he was focused on sharing and passing on the history to his descendants.

“He made sure he did these paintings to depict what was actually going on in Country,” she said.

“He did this work for our survival, because at that stage a lot of people would have died out and Barak died in 1903, he was about 85 years old. So that was his way of capturing anything that he thought that would be lost.

“We were told that we couldn’t speak our language, we couldn’t do our hunting, we couldn’t use traditional medicines or anything like that. He was just trying to give the information to us knowing that it may not have survived.”

Barak’s artworks formed a collection, telling the history of Wurundjeri using Earth pigments and charcoal mostly seen throughout many of the works placed at the National Gallery in Victoria.

The shield itself represents Aboriginal lore and custom, particularly when someone entered Country.

“When someone would come onto Country and they realised they were all great persons, they would break their spears and then that couldn’t be used on them and that was a sign of friendship. The way I see the shields is they are a part of ceremony as well.”

Jacqui said with the artworks returning to Wurundjeri, where she expects they will join Barak’s other works at the National Gallery, she said it is time for people to learn about the man and the leader.

“When I first started reading about Barak, I just remember thinking, ‘Oh, my God, my uncle’s an amazing, honourable man and it’s a really proud day today.

“I think everything’s aligning at the moment and I think Barak’s really trying to tell his story. He’s trying to reawaken everyone. We always say before we came back onto Coranderrk in 2000, the place had just been sleeping.

“[We need] to keep Barak’s dream alive and it’s not just the Wurundjeri people, it’s everyone in Melbourne who really needs to find out more about Barak. He was a wonderful man in all different ways and he did everything in a peaceful way.”