By Mikayla van Loon

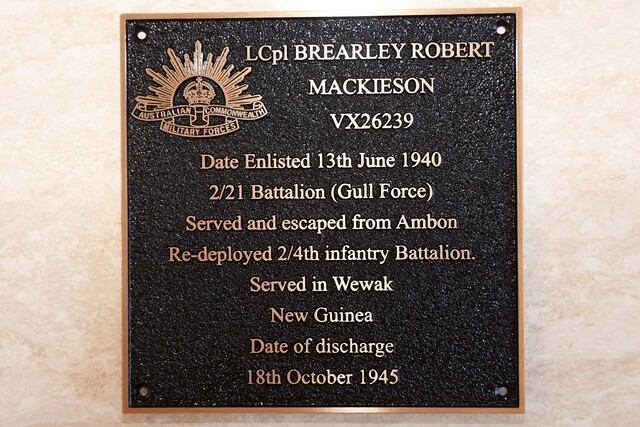

The remarkable but untold story of Brearley Roberts Mackieson, father of Lilydale RSL members Bill and Don Mackieson, has been immortalised in a plaque donated by the sub-branch.

Born 1 May 1913, Brearley Mackieson grew up in the small East Gippsland town of Buchan and from his mid-teens was working in cattle transport.

“When he was 15 years old, he used to drive cattle from Jindabyne all the way to Bairnsdale by himself,” Don said.

Not realising it at the time but that experience would set him up for what he was about to endure as a man in his late 20s.

On 12 June 1940, Brearley had heard of the invasion danger Australia was facing during World War II and so decided to enlist in the Australian Army.

Part of the 18th draft in Sale, Brearley was sent to Caulfield and then onto Shepparton where he was assigned to 2/21st Battalion.

From there the troops took the longest route march ever attempted by the Australian Army, marching 120 miles from Trawool to Bonegilla.

He was deployed from Bonegilla to Darwin, after one final farewell in Buchan, on 22 March 1941, arriving in the northern capital on 8 April 1941.

In December of that year, the Battalion was sent to the pacific island of Ambon, landing in what he described as “the beautiful and sunny” island on 13 December, seven days after the Japanese declared war.

The Gull Force, as they were known, camped under thatched roof huts and “every tree [was] laden with coconuts”, Brearley documented.

Under the command of Lt Col W Scott DSA – a World War I veteran – a request of more reinforcements was approved, with 30 extra troops joining the Battalion in Ambon, of which Brearley said in notes, only 12 had ever shot a rifle before.

With only 20 automatic weapons, the Australians were unprepared for what was coming.

At around 2am in early January, a Japanese air raid, bombing the airstrip and “strafing the huts” triggered the beginning of a bombardment.

“Our troops make for their slit trenches, a queer thrill running through them as they experience their first encounter in real war,” Brearley wrote.

A week goes by before the Japanese strike again during daylight, with 26 bombers and 12 fighters flying over – all the Australians had were two allied planes, both which came down in flames.

By the end of January 1942, a Japanese invasion was imminent. It came on the 30th of the month, with 51 ships and some 23,000 troops heading for Ambon.

The near defenceless 1400 Australian troops were “ill fated” but put up a fight using an American donated browning machine gun deterring one Japanese destroyer, which then hit a mine sinking the ship.

A well-directed order from Captain Phillip Miskin to hide in the shadows until Japanese troops were ashore and unaware of the waiting gunners resulted in a small Australian victory but five days of no food or water led to the general surrender to the enemy.

Nearly 300 troops, where Brearley was part of C Company, were dispersed to defend Laha airfield from the some 6000 Japanese. After days of bombing and fighting, the flag of surrender had gone up.

Brearley, however, alongside three others made an escape plan.

Frank Ogilvy, Jim Drummy, Harry Ault and Brearley travelled up a dry creek bed through the jungle. Brearley developed malaria fever and dysentery that would plague him all the way home.

Reaching the town of Ambon, the villagers instructed these soldiers to take a canoe and head for the island of Ceram – 14 miles north of Ambon.

Setting out after dusk, the unthinkable of the tide changing and sending them straight back to Ambon was a risk but by 2am the waiting was over and the four Australians were able to make their break for the new island.

Having to pretend they were fishermen as Japanese crews patrolled the ocean, watching as Japanese planes flew overhead on 19 February to bomb Darwin, fearing their safety from both the Japanese and head hunting tribes and not sleeping or eating for days were just some of Brearley’s memories.

On the other hand, he told of how villagers were often accommodating, offering clothing, food and beds.

Island hopping for three and a half months, stealing food when they could, eating alive fish and going without water, Brearley and the three men landed in Australia at Karumba in the Gulf of Carpentaria, met with loaded rifles from their countrymen until identification was confirmed.

Meeting his son Bob for the first time on arrival home, Brearley was then hospitalised with malaria fever, which happened on many occasions.

Of the 1396 Australians who fought in Ambon, 600 were killed in action and another 500 died in prisoner of war camps, seeing only 305 return to Australia after the war.

The casualty rate is said to be one of the highest, with Brearley stating it was roughly 20 per cent more than the losses recorded in the Light Horse Brigade charge.

Bill said it was his father’s understanding of the night sky from his time moving cattle through Victoria and New South Wales that helped lead them home.

“When travelling by boat under the stars he knew which way to go,” he said.

“He was a real Snowy River cattleman.”

Despite his malaria, Brearley was once again deployed, this time to the 2/4th Battalion in New Guinea but the illness stayed with him and he was eventually discharged at the end of the war on 18 October 1945, landing in Brisbane the day peace was declared.

Brearley Roberts Mackieson’s plaque, Bill said, was to return to his home town’s avenue of honour in Buchan South.

“It’s all these trees and seats along each side and this will be screwed onto one of the seats, where his cousin is on one part of the seat and he will be on the other,” Bill said.

“We’re ever so grateful to the RSL.”