The power of music for children and adults with a disability cannot be understated according to a Yarra Ranges music therapist and her client.

Fletcher, 14 and his mum Kim have seen and experienced this firsthand over the last four years.

Music therapy has been part of the suite of therapies Fletcher has accessed for his severe autism and anxiety since 2020 and Kim said the benefits can’t be recreated by any other support.

“It’s an evidence based practice to help humans self regulate and there’s something neurological that really can’t be replicated by any other inputs,” she said.

“It works on so many levels, so the connection with others, it helps with regulation and managing anxiety and functional skills.”

It was for this reason they were so baffled by a recent Federal Government change to the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) structure for music therapy and who can access it.

The Australian Music Therapy Association (AMTA) said it discovered on Friday 22 November that the NDIS will remove music therapy from the Capacity Building – Improved Daily Living category.

The price guide change, effective from 1 February 2025, will see the one-on-one hourly rate shift from $194 to $67 but a group rate, of four or more participants, be able to be charged at $194.

In a statement on Tuesday 26 November the NDIS said participants and providers can still access current arrangements until 1 February.

“Participants who have art or music therapy stated in their plan, because it is reasonable and necessary and based on evidence in their specific circumstances, can continue to access supports at the higher rate,” it reads.

“While art and music therapy remain permissible, they do not meet the evidentiary standards required to be classified as a ‘therapy’ under the definition of NDIS supports.”

Cath Russell, a practicing music therapist since 2006, said to discount music therapy as “social participation rather than a therapy is just not acceptable”.

“There’s a bit of misinformation out there at the moment, Bill Shorten has been on radio and trying to push this claim that we’re not an evidence based profession,” she said.

“It’s a bit disheartening. What’s really disheartening is there’s about 50 years of university research in Australia into music therapy as an allied health profession.”

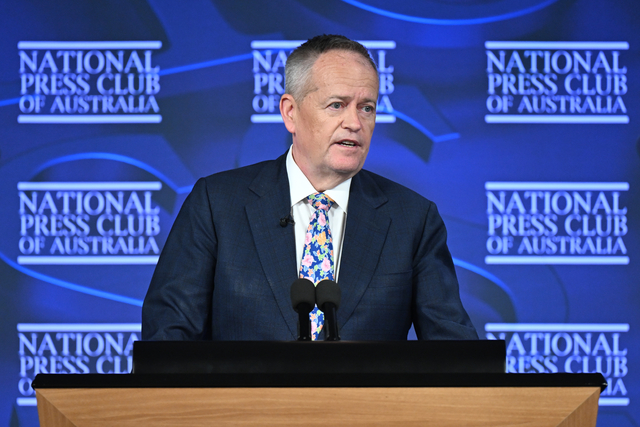

In speaking with ABC Radio Melbourne on 27 November, NDIS minister Bill Shorten said the decision wasn’t based on budgets but rather proving this form of therapy was having the best outcome for the participant.

“There’s 680,000 people on the Scheme. At the moment, 7000 do some form of music therapy. It’s – $16 million is paid out annually. Like, this is not about budget cutting. That amount of money is not the issue,” he said.

“What we want to do – and it’s not just in the music sector – we’ve been, for the first time ever in the Scheme, we are now clarifying what you can spend money on and what you can’t spend money on.

“If you already have [music therapy] in your plan until your plan expires, it’ll be paid at the level it was. After that, when your plan expires, if the therapist working with the allied health professionals can show that it’s reasonable, necessary, that in the circumstances it’s assisting someone’s functional capacity, they can continue to access support at the higher rate.”

Ms Russell said despite $194 per hour sounding like a lot, it’s not an hourly wage but rather covers a clinical practitioner’s insurance, admin, set up and pack up time, report writing and other embedded costs like having the appropriate equipment.

On one hand, however, Ms Russell said, the Federal Government has funded arts and music therapeutic courses to ensure practitioners are supported but on the other hand, she is concerned this will take work away from them.

The main uncertainty for both Ms Russell and Kim is who will continue to qualify for access to the higher paid, one-on-one support, especially given that people with a disability can stagnate in their progress but still be benefiting from the therapy.

“Sometimes people, even though you might provide them support, they may be able to just maintain that skill,” Kim said.

“Because a lot of skills that are taught in some capacity building, whether it be music therapy, speech therapy, OT, if people aren’t given the opportunity and the support, they can actually regress. So sometimes it’s just the maintenance of a particular thing.”

Kim said music therapy was first suggested as a non-pharmacological intervention for Fletcher’s high anxiety and since then it has become an integral part of his self-regulation practice.

“He was in a higher level of distress then, and the intervention helped with the other supports with his multidisciplinary team. Together it helped pull down his hyper arousal levels and really helped him level out and not be so distressed by his environment,” Kim said.

“Since then we’ve seen the benefits of music therapy. So it helps in the acute phase but now it’s helping him with function, it helps him proactively manage his regulation, but it also helps him with simple things like fine motor skills and also with his interaction with other people.

“It’s helped him with communication. So Fletcher doesn’t speak, he primarily uses a speech device to talk, however, Fletcher has more vocalisation during music therapy compared to any other therapeutic influence.

“The modality of music helps in a way where it provides social cues and auditory cues to participate in a shared experience. So that’s something that’s really difficult to replicate with other interventions.”

Ms Russell said in cases where children don’t speak or have sensory overwhelm or have been experiencing tantrums, music is a space where they can calm, regulate and synchronise with her.

“It’s super motivational. That’s the magic of arts based therapy, they are extremely motivational ways to reach people who might struggle otherwise to achieve therapeutic outcomes,” she said.

“Moment by moment therapeutic interventions play out through a session, and from there, the more academic and clinical side of that is assessing that and being able to communicate it effectively to the psychologist, to the teachers at school, to the OT and physio.”

Angered by Mr Shorten’s statement that “we just don’t pay people because they’re good people or because they’ve trained. It’s the outcome they have for the participant. This is not a Scheme for professionals, this is a Scheme for disabled people”, Kim said in no other profession is it outcome based nor has the criteria for a satisfactory outcome for a participant been communicated.

“I’ve actually not been told, we weren’t actually informed by the NDIS. I found out via the grapevine. They haven’t actually communicated it at all formally to participants,” Kim said.

As of Thursday 28 November, Kim said she still hadn’t received any notification of the changes nor had the NDIS portal been updated.

Ms Russell said she, the AMTA, fellow practitioners and clients have each been sending research papers to Mr Shorten’s office and the NDIS, as well as making phone calls.

“We’re making a very clear request that music therapy needs to be reinstated as a therapeutic support, that it’s not suitable to describe it as a social support,” she said.

A petition has also been started, with over 47,000 signatures on Monday 2 December. Find it at, change.org/p/keep-music-therapy-as-an-ndis-funded-therapeutic-support